The Fortress of Satu Mare

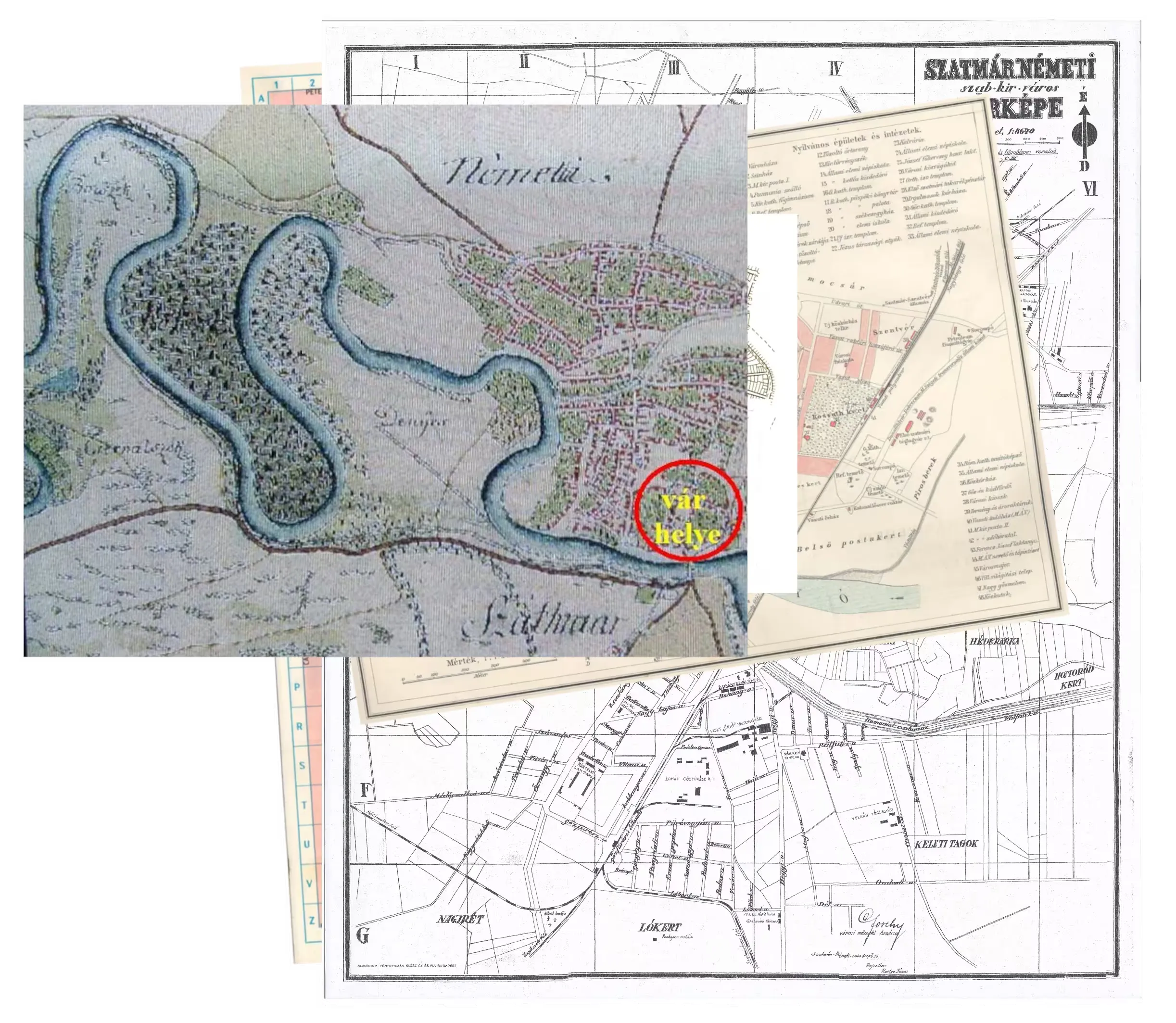

Satu Mare or Szatmárnémeti (commonly referred to simply as Szatmár) in hungarian derives its name from the merging of two settlements, Szatmár and Németi. Szatmár lay on an island wedged between two branches of the Someș river (Szamos in hungarian), while Németi was situated on the northern shore of the island. The two settlements united in 1715, becoming a free royal town.

The city’s first written mention can be found in the work of Anonymus. According to his account, during the Hungarian conquest, the leaders Szabolcs and Tas besieged the city for three days before capturing it.

From Anonymus’s notes, we also learn about the possible origin of the city’s name. Allegedly, it comes from the German word “Salzmarkt” (salt market), which aligns with the fact that salt was transported on the Somes river by rafts and boats from the old salt mines of Dej—whose upper shafts date back at least to Roman times. You can still admire one of these dugout canoes made from a single tree trunk in the courtyard of the local Fine Arts Museum. According to local tradition, it was unearthed not far from the city, along the banks of the Somes, buried in the sand.

Németi presumably began to develop in the 11th century, under the reign of King Stephen, when his wife settled German-speaking hunters in the region. Hence the name Nemeti - meaning place where Germans live.

Although the city’s name can be easily traced back to its origins, it is still challenging for most people to visualize what the area looked like in the past, when there were two separate settlements or even just a few decades ago. It’s especially interesting to examine the city’s developmental processes over different historical periods. One can consider how far back certain districts or streets can be traced.

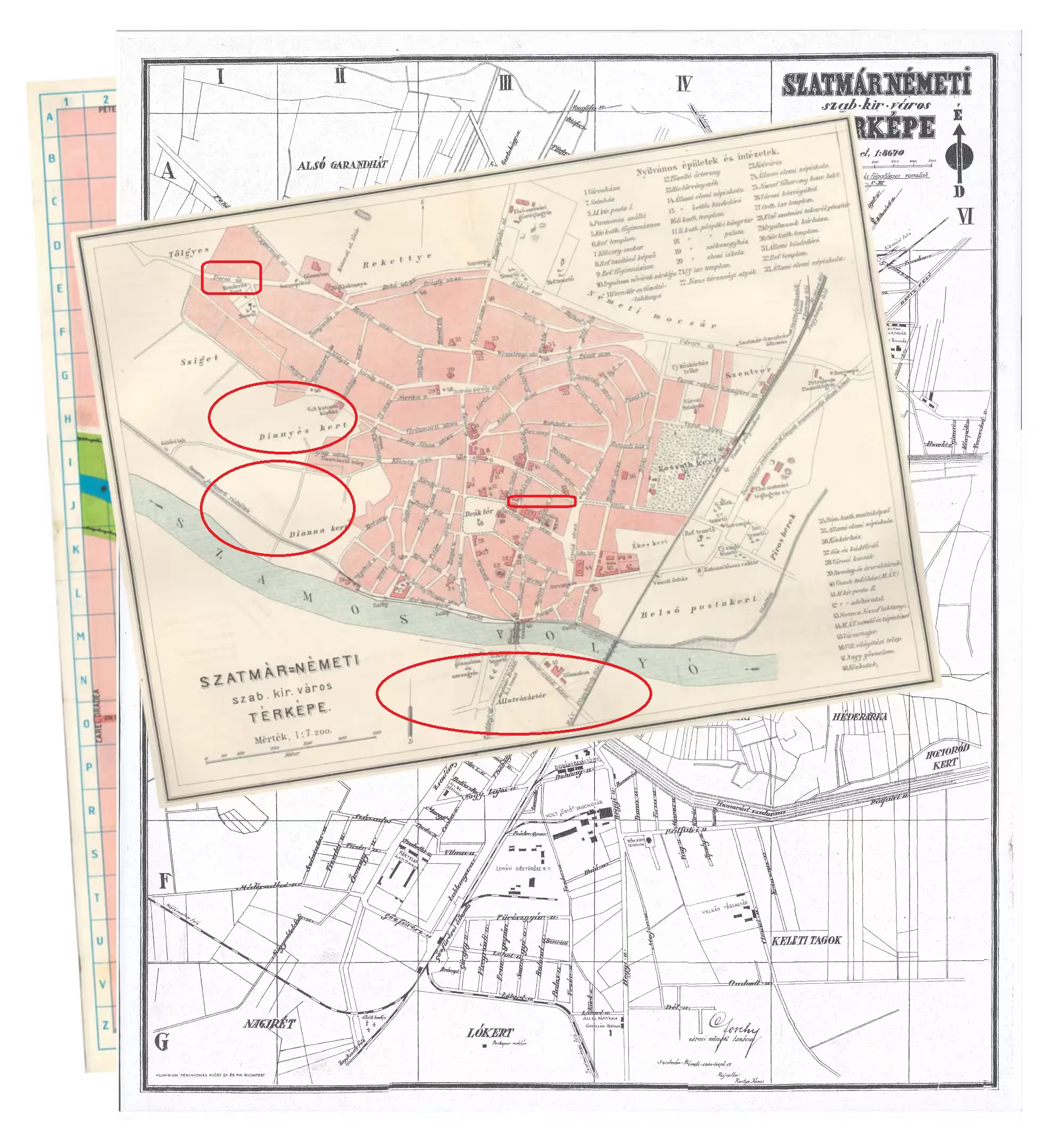

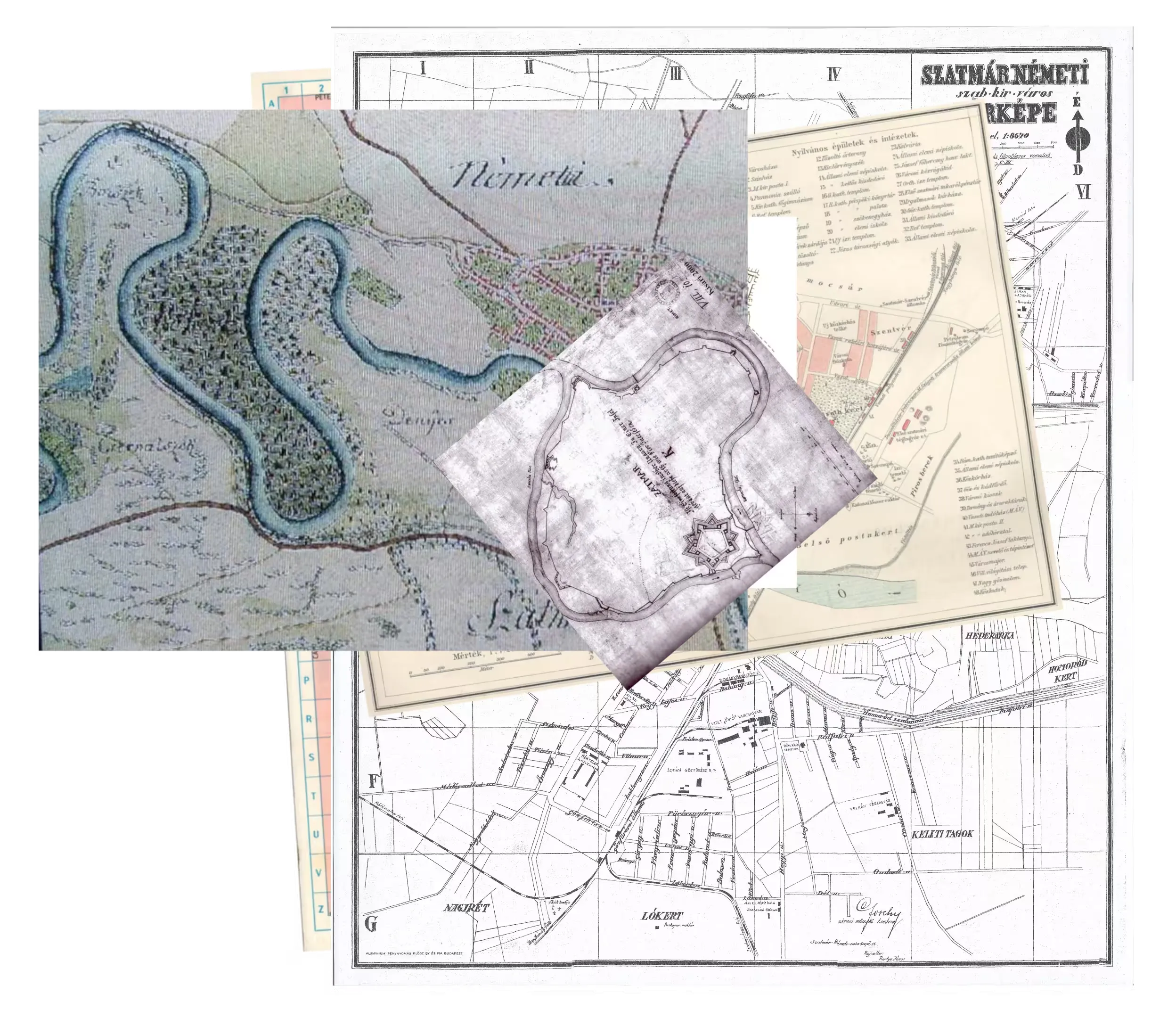

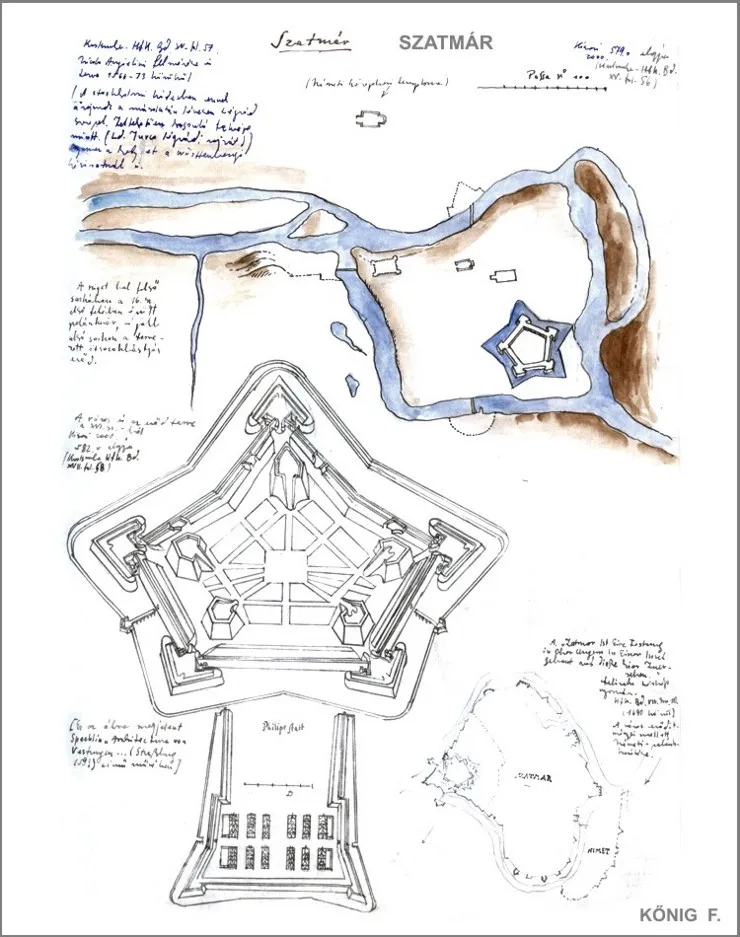

To illustrate these changes, I plan to show some maps. Let’s identify precisely where the infamous Szatmár Castle stood—a fortress everyone has heard of but no one has seen—and where that particular branch of the river once flowed between Szatmár and Németi before it was later filled in.

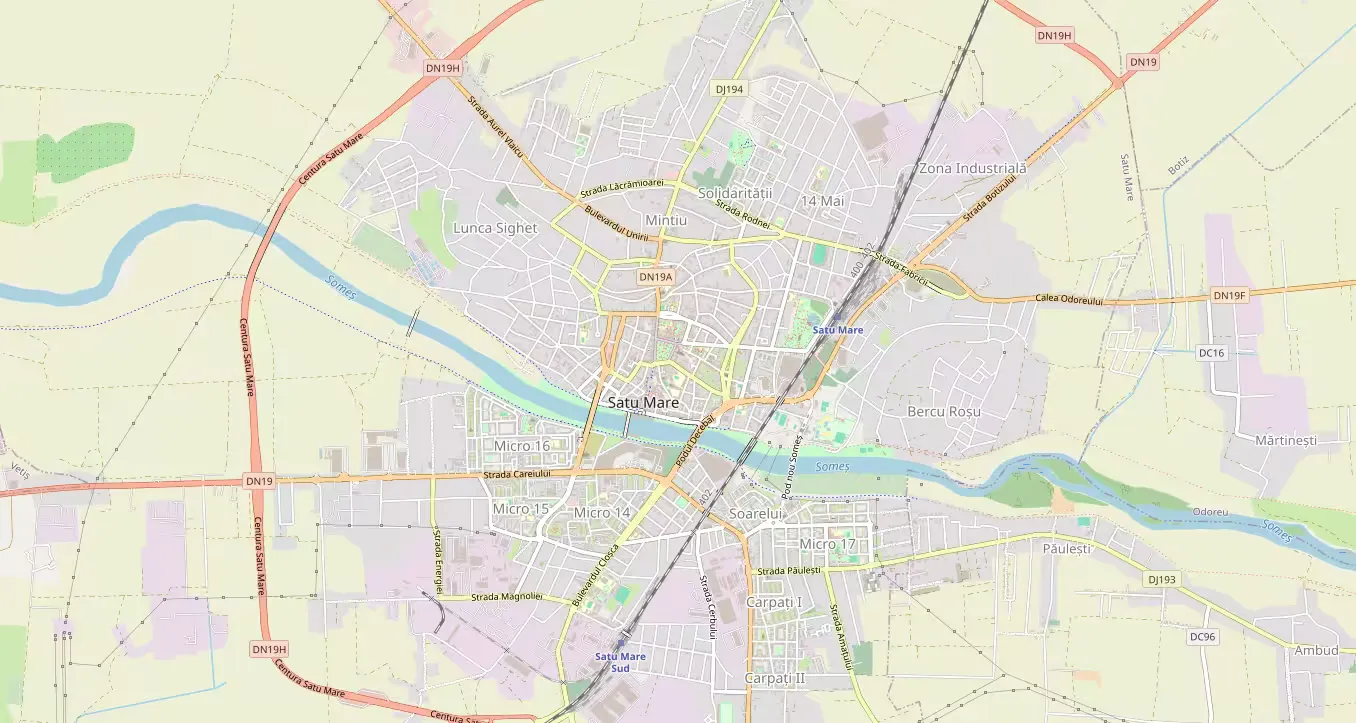

Satu Mare in 2024

Over the past twenty years, the city has undergone enormous changes, largely thanks to economic growth and Romania’s accession to the EU. Among the most important developments are the new bypass road, which curves around the city like a semicircle, as well as new bridges and shopping centers. The city’s area is expanding continuously, with more and more residential neighborhoods being built on the outskirts, mainly featuring housing complexes.

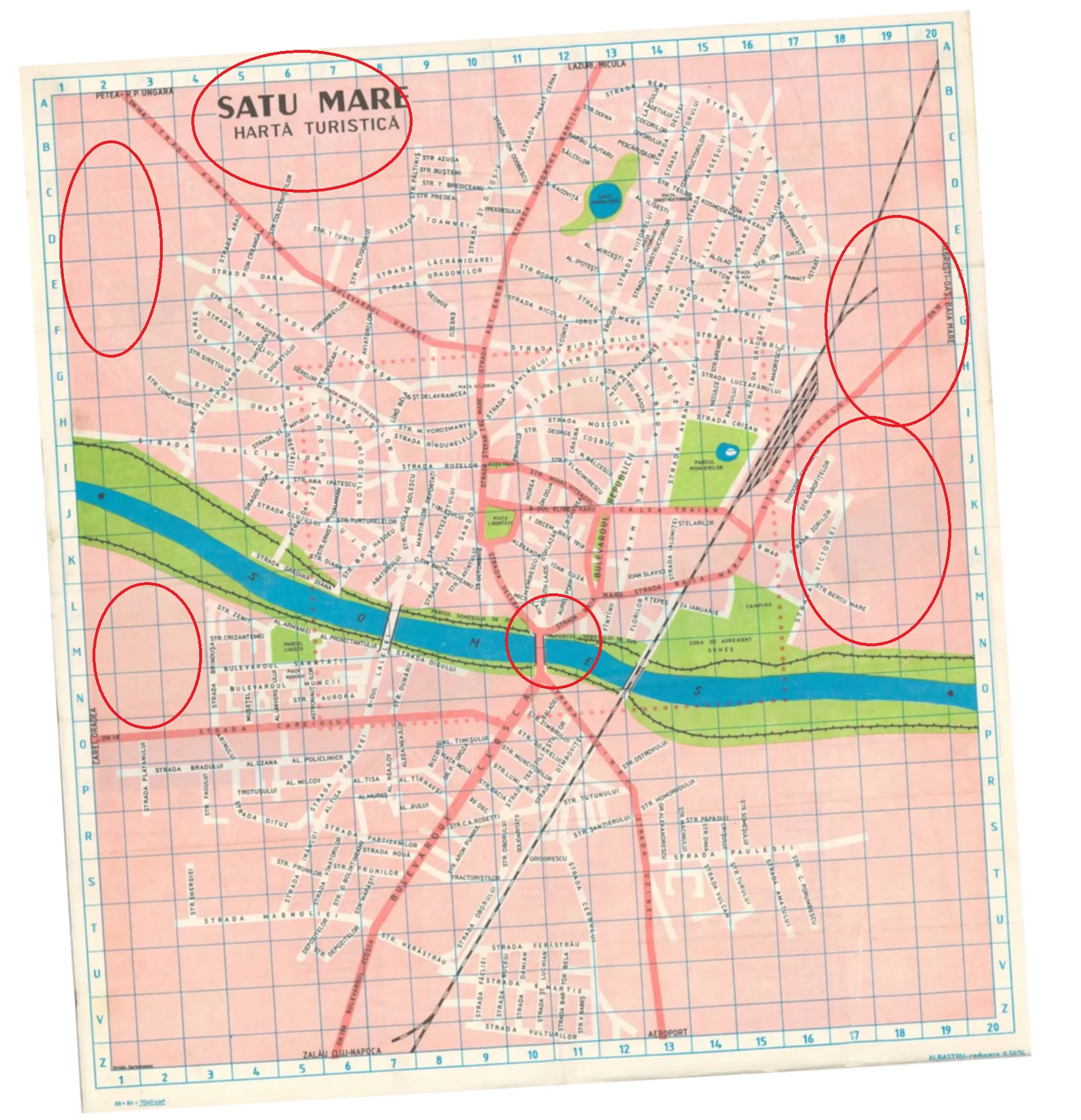

Communism and the Flood

While the city map from this period still appears quite familiar, we can detect a few subtle changes. Among them are the consequences of the great flood of 1970. Looking back in time, it’s evident that the river significantly shaped the city’s character. According to urban legends, during the 1970 flood in Szatmár, the river rediscovered its old bed, evoking old memories among the local population.

The catastrophic flood tore through many bridges and dikes as it surged down from the mountains, and Satu Mare (Szatmár) was no exception. On the map from that era, we can still see the predecessor of the Decebal Bridge, which was lower and whose northern exit did not turn eastward like the current one, but rather angled slightly west toward the city center. Along with the reconstruction efforts, the city center was also redesigned. The area between the central park and the riverbank was almost completely cleared, and concrete apartment blocks and a huge administrative building were erected there.

It’s also noticeable that the city’s boundaries were significantly narrower then. Some of today’s neighborhoods, like Pirosberek, are entirely absent from the map. There are two reasons for this: firstly, the depicted map was of a touristic nature, not aiming for complete accuracy; secondly, certain districts were not yet significant at that time. Instead of residential buildings, orchards and farmland occupied the areas where later neighborhoods would be developed.

Satu Mare Between the World Wars

During this era, the city’s sovereignty changed hands multiple times between the Hungarian and Romanian states. Each such change brought alterations to the names of streets and squares. Thus, some old street names remain alive in the collective memory, while others have been forgotten.

Every Hungarian resident knows the name of the largest city park, Kossuth-kert (Kossuth Garden), while almost no one remembers the old name of the central park. Locals simply refer to it as the “old center.” This is probably because it received a new name with every change in administration. During the Monarchy, for example, it was called Deák tér, while during the war it was renamed Horthy-tér, as shown on the attached maps.

The names of streets often changed as well. The former Pázsit Street was renamed Párizs (Paris) Street by the Romanian administration, while Pelikán Street was faithfully translated into Romanian—likely because they assumed it referred to a bird, unaware that it originally honored a respected local citizen who lived there in the mid-19th century.

In addition to the name changes, the absence of residential districts is also striking. During the Communist era, numerous new apartment blocks were built, mainly on the southern side of the river. New bridges were constructed to connect these newly built neighborhoods with the older parts of the city. Although river regulation began centuries earlier, after the wars the floodplain was further narrowed and new embankments were constructed, which had to be modified again following the 1970 flood.

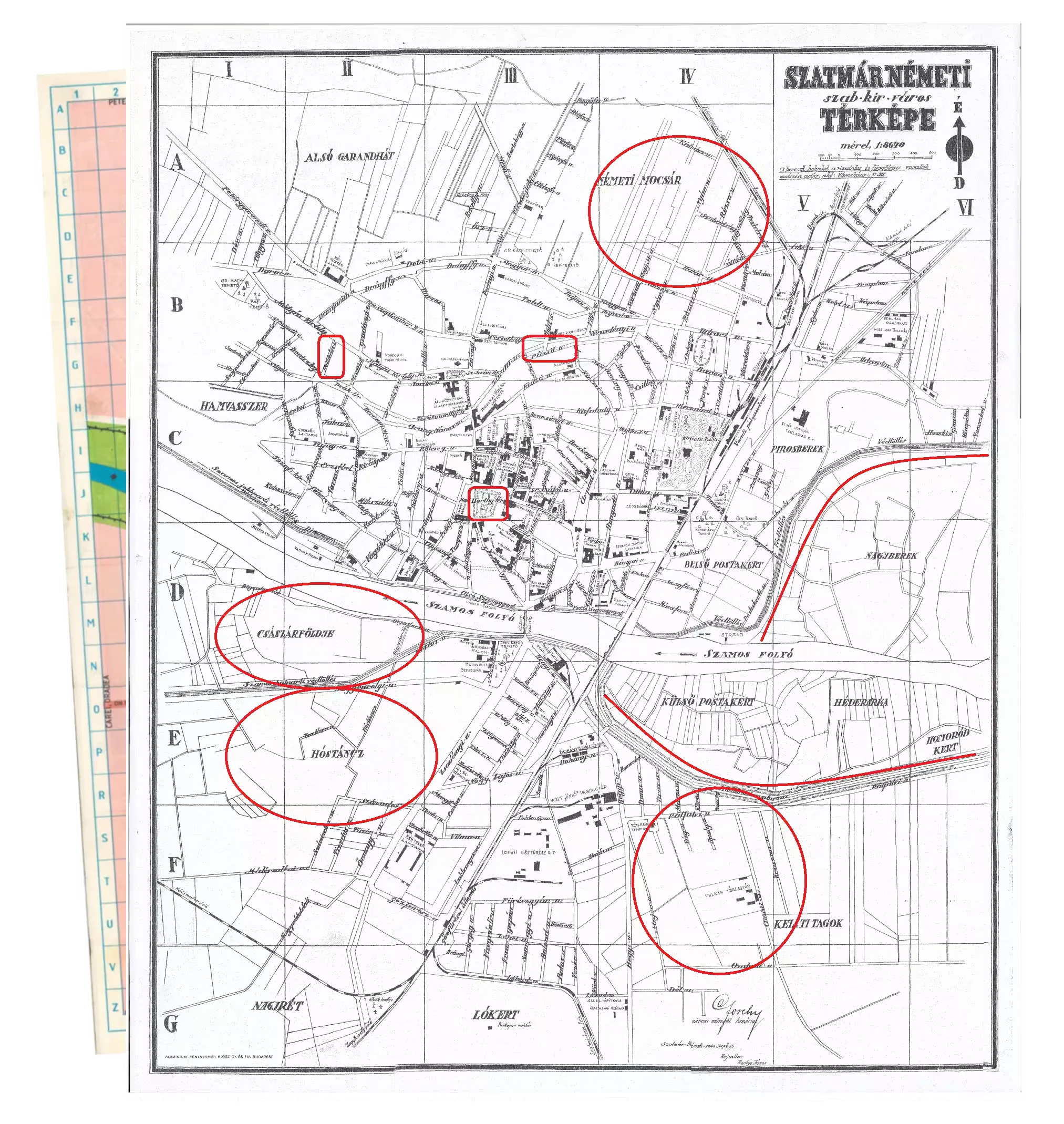

Satu Mare at the Dawn of the 20th Century

The next map shows the city in the last years of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. It no longer depicts areas south of the river. The Civil Servants’ District (Tisztviselőtelep) is shown in only a rudimentary form, while to its west the main roads are marked but no residential buildings are present. At that time, this area was referred to as “Diannakert” and “Dinnyéskert” — used for small scale agriculture and faring, and it would later become a fully developed suburban neighborhood.

Back then, Darai út (Darai Road) really did lead to Dara and was one of the main routes if one wanted to leave the city heading west. Nowadays, you cannot leave the city via that road.

The railway line had western branches in both the northern and southern parts of the city, which were later dismantled. Their remnants can still be detected on satellite images, as well as beyond the border in the towns of Csenger and Zajta, which have now become terminal stations where railway traffic is in decline.

At that time, no direct road led from the city center to the railway station. Later, a completely new street was opened (today’s Boulevardul Ion Constantin Brătianu), flanked by apartment blocks. These buildings form a sharp contrast with the surrounding monarchist-style Bishop’s Palace and the Courthouse.

Apart from these changes, one can also observe the original names of streets and squares. Some of the most important ones are still remembered by the residents today (e.g., Mátyás király utca, Honvéd utca, Kölcsey utca), while others have completely sunk into oblivion, such as Attila út or Külső sor.

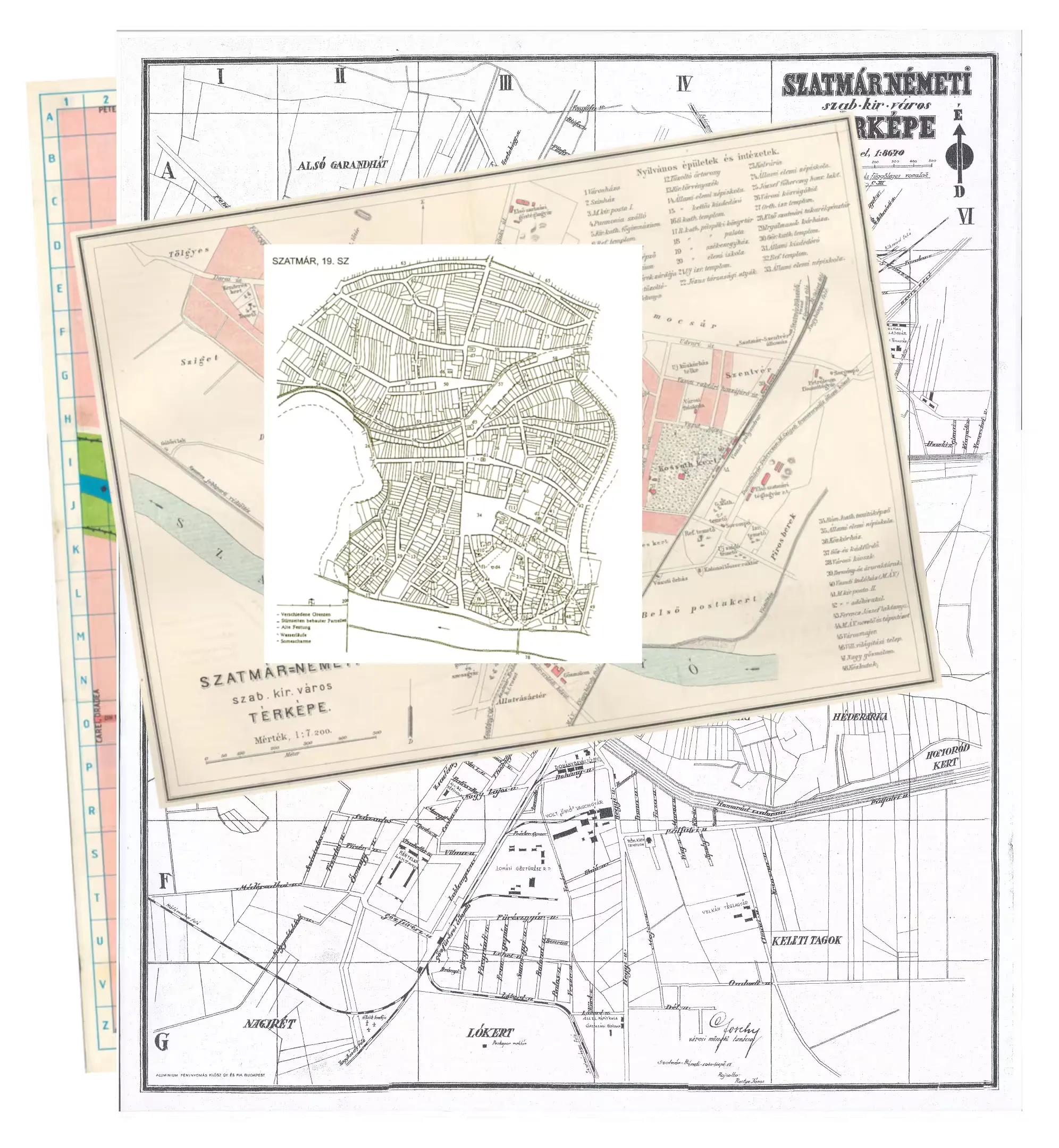

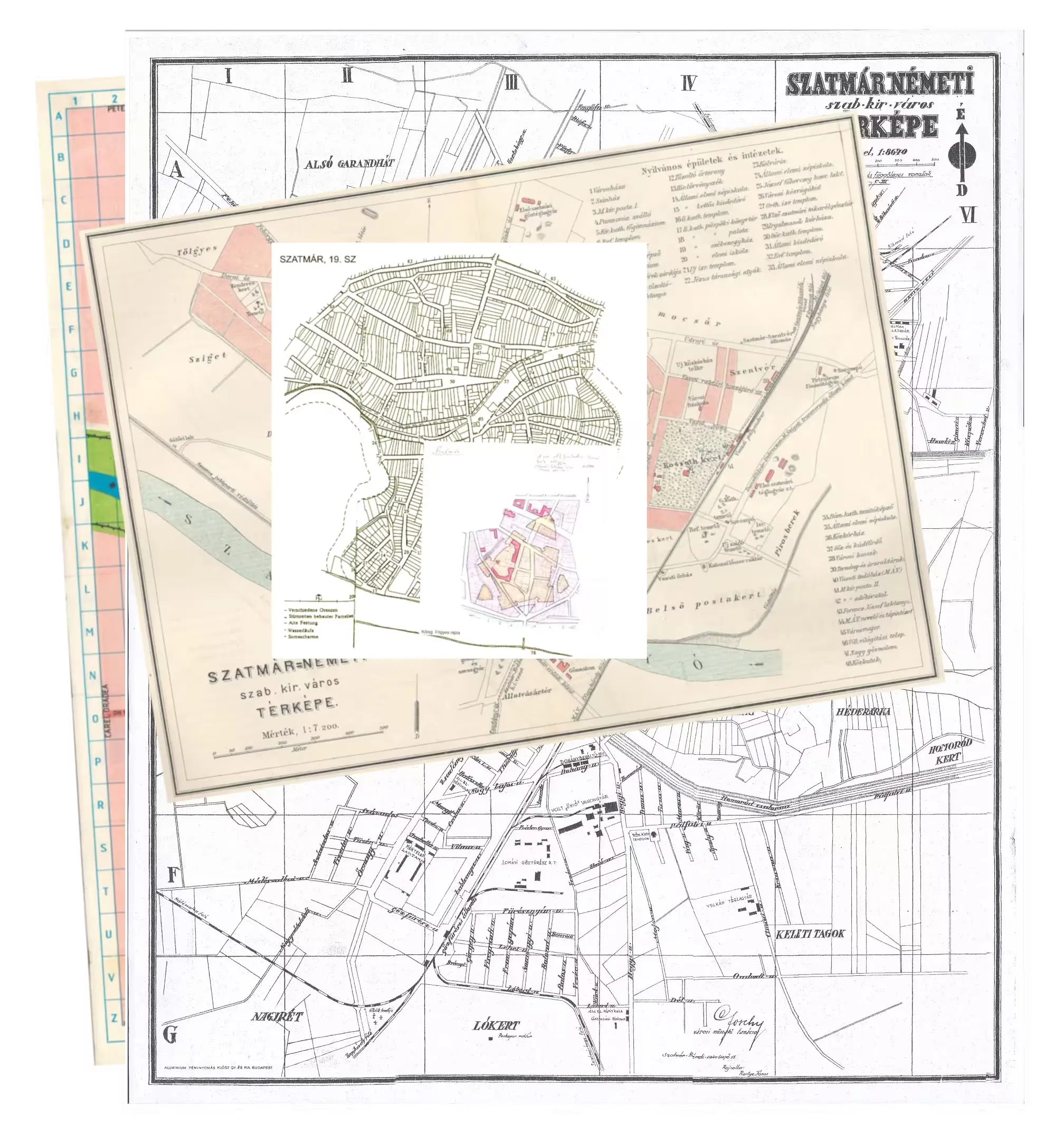

Satu Mare in the 19th Century

The city also underwent significant changes during the 19th century. The further back we go in time, the harder it is to form an accurate picture of how the city looked. The map presented here attempts to summarize a century of development in a single moment, which is almost an impossible task.

This was the era when the railway network was built, and when Bishop János Hám worked on the city’s modernization. At that time, the roads were still unpaved, and students leaving school had to balance on wooden planks placed on the street so as not to soil their robes with mud. The Bishop’s Palace and the Cathedral were built during this period.

On the map, faint lines indicate the old branch of the river, which had already long been filled in. It is clearly visible that today’s seemingly chaotic street layout had a good reason for being the way it was. Streets originally followed the river’s banks, and when the northern branch of the river was filled in during the 18th century, new roads and gardens appeared on the newly gained land. Many of these plots ended up in the possession of the church. The Zárda (Convent) Church and the girls’ college, for example, were built on precisely such reclaimed land.

At the beginning of this era, the Németi and Láncos (Chain) Reformed Churches were also constructed. This came about because for a long time the Reformed community was not allowed to build stone churches. As soon as they were permitted, they quickly erected the long-awaited, more durable places of worship. The Chain Church was built on one of the highest points of the former Szatmár island, while the Németi Church was established in the heart of the Németi district that gave it its name.

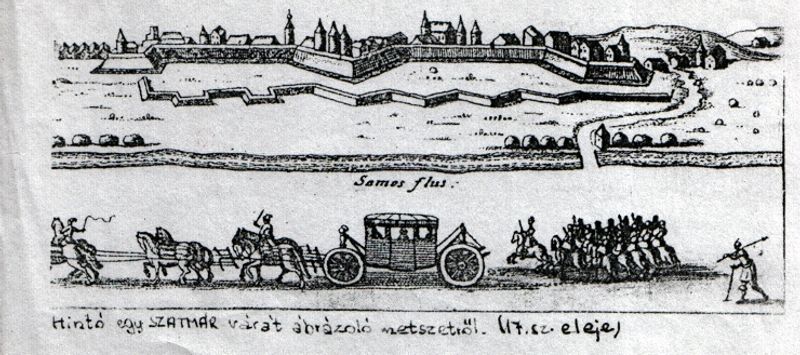

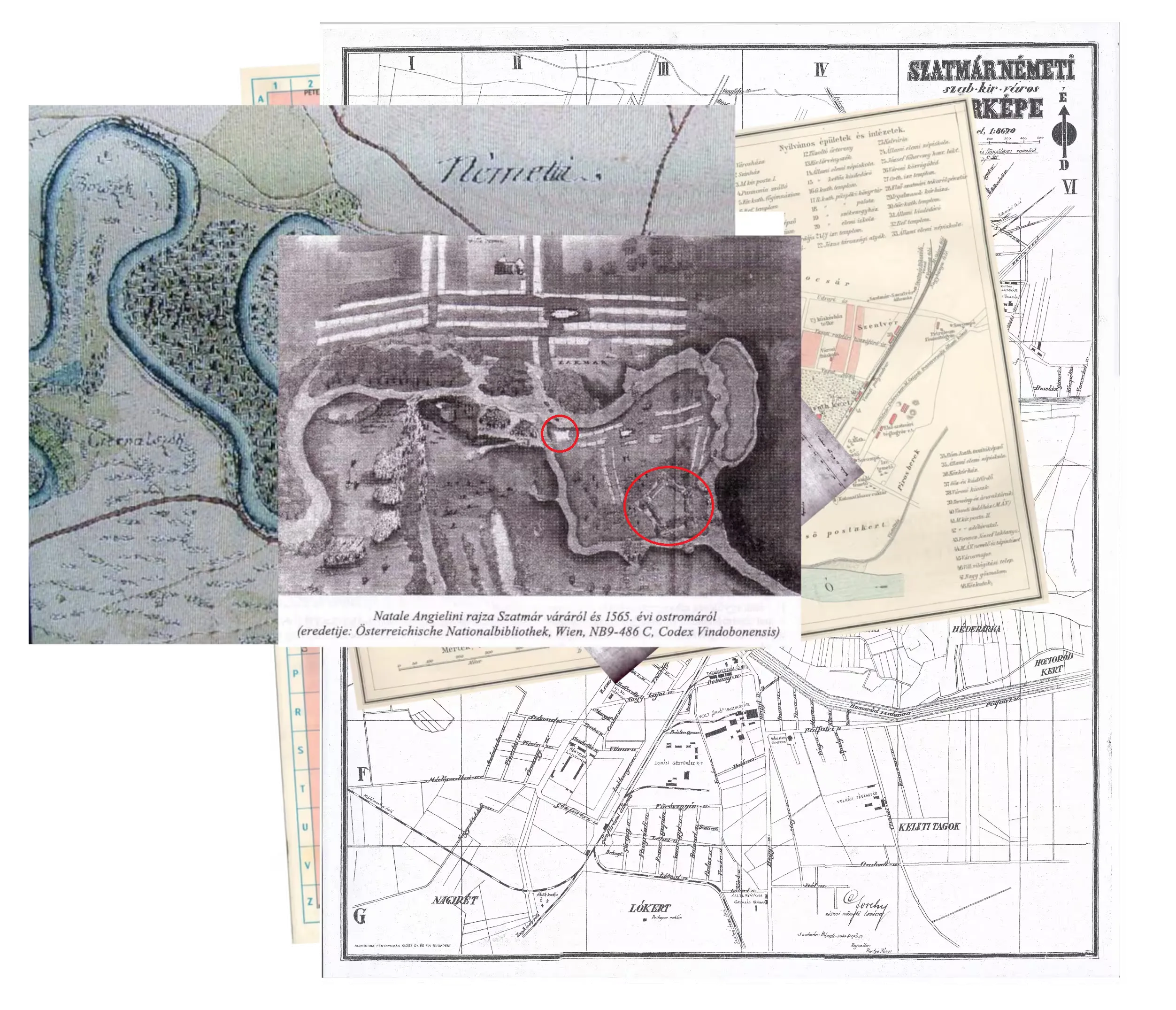

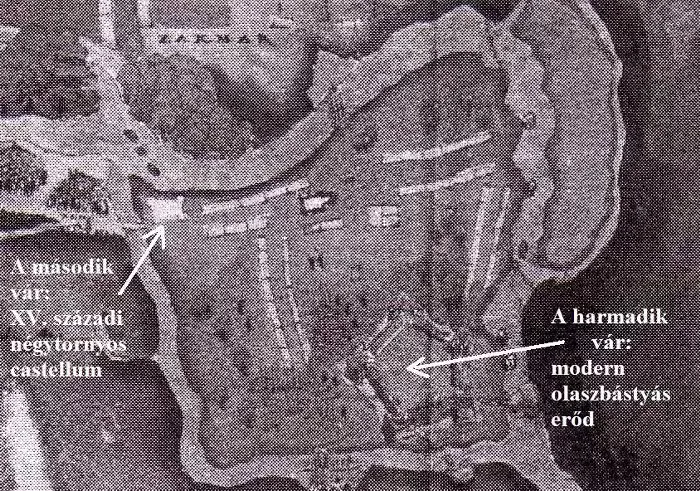

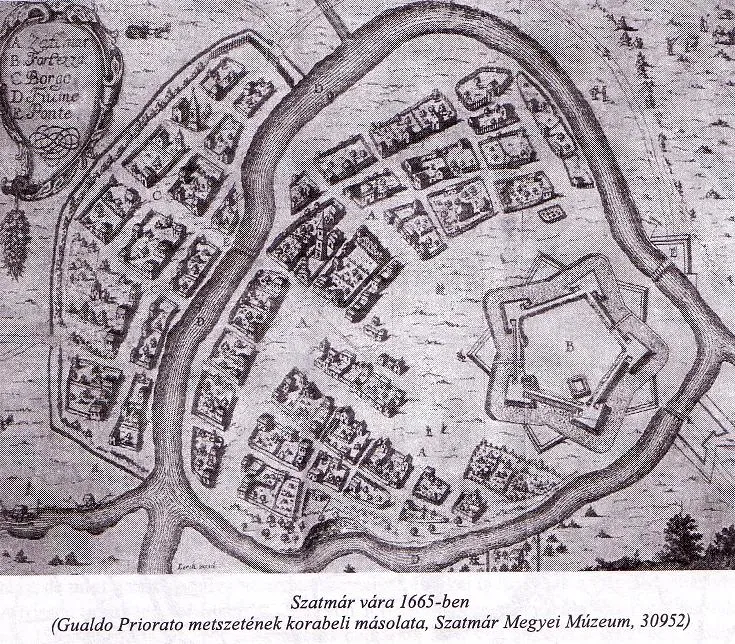

The map below shows the floor plan of the old fortress, whose northern tip reached as far as today’s cathedral, while its southern side extended to the river. It was a star-shaped fortification made of earth, completely demolished in the 18th century.

Satu Mare in the 18th Century

As mentioned, the city we know today was formed in 1715 by the union of Szatmár and Németi. At that time, one branch of the river still separated the two settlements (this branch was later filled in). At the end of the 18th century, river regulation work began on the Somes (Szamos). This started under a decree of Empress Maria Theresa, which required the removal of all structures and mills from the river, as they hindered the free flow of water. Later, in 1783, Count Antal Károlyi began the actual riverbed regulation by cutting through a bend in the river in the Postakert area east of the city. Although the bends in the western part of the city were cut later, river regulation continued well into the 19th century.

The Fort

The original significant fortification of the castle was due to the Báthory family, who acquired it in 1543. At that time, the island of Szatmár was reinforced, and a strong earthwork fortress was constructed. Subsequently, the castle changed hands several times and endured numerous sieges. Finally, in 1565, the defenders themselves set it on fire so that it would not fall into enemy hands.

The fortress attained its modern, five-sided star shape in the second half of the 16th century, thanks to the plans of the famous Italian military engineer Giulio Baldigara, who served the Habsburgs for a long time. Later, the renewed fortress was besieged multiple times, and although Prince Ferenc II Rákóczi ordered its destruction more than once in 1705 and 1706, these attempts were unsuccessful. Eventually, in 1711, the Károlyi counts set it ablaze, and it was completely destroyed. Today, nothing remains of it.

On the 1565 siege depiction, a second, stone-built citadel can also be discerned—a typical medieval, rectangular fortification built before the age of artillery in the 14th–15th centuries. Presumably, even before that, various wooden and earthwork defenses stood on the island, but unfortunately no trace of them has survived.

Attachments and Sources

Below are several maps and images of the castle, which help provide a visual understanding of the city’s historical layout and the castle’s location. I have also included a few links that offer additional insights and more detailed information. Since this is just a blog post, I do not aim for a complete, scholarly listing of sources; these references are intended more as inspiration for those interested.

On the Regulation of the Somes River

Ready to get started?

I'd love to hear about your project. Let's chat!